U.S. Soybean: Caught in the Crossfire of Trade Wars

The deal with China offers a fragile reprieve for U.S. soybean producers, but the sector remains acutely vulnerable to government shutdowns and punitive tariffs.

Donald Trump may claim to be a master of the deal, but Xi Jinping has proved just as skilled at getting under his skin. On October 29, just hours before the meeting between the two leaders, Beijing sent a small signal of appeasement, purchasing three cargo ships scheduled for delivery between December and January. This purely symbolic volume ended a six-month halt on American soybean imports.

Confirming Donald Trump’s statements after his meeting with Xi Jinping, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent specified that China plans to buy 12 million metric tons of soybeans from the United States by January 2026, then 25 million metric tons per year. The final version of the agreement is expected to be signed in the coming days. “Our great soybean farmers, who the Chinese used as political pawns, that’s off the table, and they should prosper in the years to come,” Bessent said in an interview on Fox Business Network.

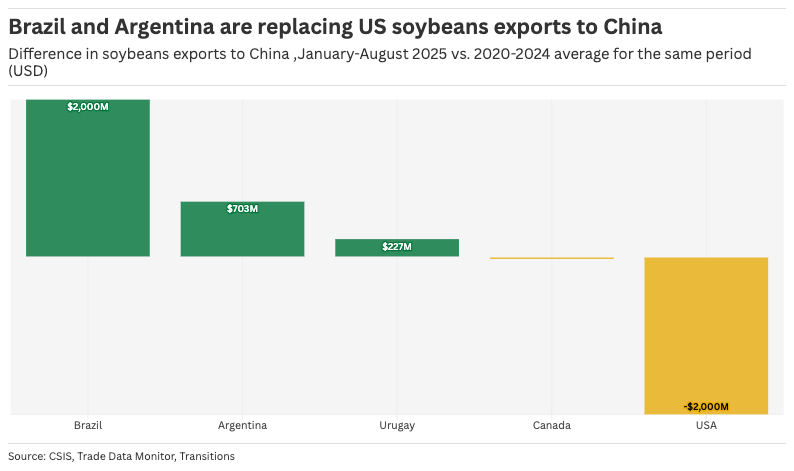

Chinese authorities have provided no details on the three-year agreement. Crucially, the issue of tariffs on U.S. imports was not addressed. The current tax level—a total of 34%—is critical, as it determines the competitiveness of U.S. soybeans against rivals whose tariffs entering the Chinese market are below 15%. “Before China applied its tariffs, the price difference between U.S. and Brazilian soybeans leaving their respective countries was negligible, with FOB (Free On Board, Ed. Note) prices standing at $407 vs. $405 per ton as of October 20. The loss of competitiveness does not stem from the market, but from the tariff barrier itself,“ stresses Gautier Le Molgat, France Director at Argus Media. This omission is not unprecedented. During the “Phase One” trade deal in 2020, retaliatory tariffs were never fully lifted, which left U.S. soybeans structurally disadvantaged. Without a complete tariff waiver, these new commitments could easily remain mere promises. This experience undoubtly explains the cautious reaction from the American Soybean Association (ASA).

Trade wars leave their mark

The preceding trade episode had lasting consequences. The Cato Institute estimates that U.S. exports were reduced by $27 billion, with soybeans accounting for 71% of that loss. “The combination of abundant production and slower-than-expected demand growth, even at historically low prices, is worrying. The risk of a reduction in planted acreage in 2026-2027, and thus a supply shock, is real because producers are currently disheartened by negative margins across many agricultural products this year,” explains Gautier Le Molgat.

“Soybeans have always held a strategic role. In the 1970s, during the Tokyo Round, the United States imposed an embargo to highlight Europe and Japan’s reliance on this protein source. Intensive livestock farming in Europe had been dependent on soybeans since the 1950s. By tripling its price, the embargo caused a lasting shock throughout the supply chains. It was also during this period that Europe encouraged Brazil to produce soybeans on a large scale.”

Philippe Chalmin, Professor Emeritus of Economic History at Paris-Dauphine University

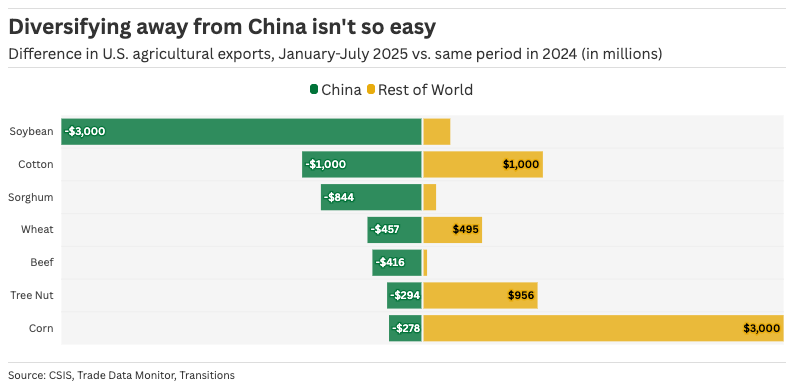

As early as 2018, China accelerated its diversification strategy. Following Europe’s example in the 1970s, it shifted its focus to Brazil to secure its supply (see insert), while also supporting the development of Brazilian port and rail infrastructure. The U.S. share of Chinese imports has fallen below 25% in 2024, down from 50% in 2017, while Brazil and, to a lesser extent, Argentina, have seen their market share surge.

Meanwhile, the United States has failed to find new export outlets; China absorbed more than half of U.S. soybean exports in 2024, a reality highlighted by the drop in Chinese imports in 2025.

“The Trump administration’s room for maneuver to find export markets is limited. Moreover, regardless of the outcome of negotiations with the United States, Chinese demand is likely to stagnate,“ confirms Simon Lacoume, Economist at Coface. Indeed, China faces demographic decline, having lost over 4 million inhabitants in the last three years. Furthermore, Beijing is pursuing a policy of optimizing animal feed, seeking to limit the protein content in soy meal. These two trends—one structural and the other strategic—place a durable ceiling on future demand.

The Crisis is Also Domestic

The prospects for the domestic market are no more promising. The agricultural sector is penalized on two fronts: while farmers await emergency bailouts in 2025-2026, similar to those of 2019-2020, they are suffering the consequences of the government shutdown, which freezes the potential disbursement of funds announced at the beginning of October. Concurrently, the design of aid mechanisms, though made more favorable by the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB), renders federal support for the soybean sector largely ineffective.

“Crush, Baby, Crush”

Faced with export market turbulence, the domestic biofuel sector could provide a sustainable alternative. The EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) published new proposals for the 2026-2027 Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) program in June. The increase in mandatory targets is set to boost total biofuel demand by about 5 to 6%, meaning an additional 9 to 10 million tons of soybeans could be crushed by 2027.

Caught between high production costs, estimated at $12 to $13 per bushel, and market prices that struggle to exceed $10 per bushel, farmers have so far favored storage, betting on a future price rise or the arrival of a federal subsidy. “During the previous trade war with China, American farmers did not hesitate to aggressively stockpile their soybeans due to a lack of buyers. Stocks surged from 12 to over 25 million tons between 2018 and 2020 before falling back to around 15 million. As of September 30, 2025, they do not exceed 9 million, leaving some margin for holding onto the harvest today,” notes Gautier Le Molgat.

Default Filings on the Rise

Farm bankruptcies filed under Chapter 12 (Chapter 12 Bankruptcy), a procedure reserved for family farmers, are accelerating, increasing by nearly 96% nationally in the first quarter of 2025 (88 filings), compared to the same period in 2024 (45 filings).

This pressure is concentrated in the most fragile regions: Arkansas is one of the hardest-hit states, recording 15 filings in Q1 2025 alone, a number close to the state’s total for all of 2024.

This issue is highly sensitive on the national political stage ahead of the midterm elections. The political impact is exacerbated by a structural factor in Congress: the overrepresentation of rural America. As Philippe Chalmin highlights, the fact that every state has two senators, regardless of its population, grants agricultural states significant political leverage in budgetary and commercial negotiations. This institutional reality makes the Senate particularly sensitive to farm defaults, intensifying pressure on the White House to quickly release the promised aid and find new markets. While the unblocking of Chinese imports offers a breather to the Trump administration, it fails to solve the structural problems of an agricultural sector facing increasing competition in its export markets.

Curious about how trade wars, energy transitions, and global finance intersect? Join Transitions and get expert analysis delivered weekly in both English and French.